Free time and chance found me on twitter in the last week, in the middle of a fiery storm about the need or influence of local language education. Apparently, there is a new initiative among political leaders of South Western Nigeria to re-instate Yoruba language education in primary and I think university education (among other pan-Yoruba political and socio-cultural initiatives). Social media reaction to Nigerian politics (as I believe politics of every country) has usually oscillated between the derision of any concrete plan as a waste of public time and funds, and a strong condemnation of most of them as wasteful spending. Good policy decisions rarely make waves. In this case, the part of the discussion about language use caught my attention, and I jumped in.

I’m not fiercely Yoruban (to use an Americanized adjective), and evidence to the inevitability of hybridity are overwhelming enough to silence any hegemonic crusade. None of the efforts by the inviolate French Academy over the course of its life has stopped the evolution of French in places where it is spoken by non-native speakers. Speakers of that same language from Congo, Rwanda, Ivory Coast and Cameroon will probably find themselves using “pardon?” more times than necessary within the course of a usual informal conversation due to the influence of slangs and vernaculars not common to all of them. The Arabic language spoken in Morocco is not the same as the one in Egypt. Ask an Iraqi and a Saudi to converse in that common language and watch them stutter and lean into each other to be sure that they are picking up the same intention from words that used to mean the same things hundreds of years ago. It is the same for the Portuguese in Portugal as compared to the one in Brazil, or the French in France as compared to Canada, or to the Spanish of Spain as compared to Mexico, Venezuela or Argentina. The common fact to all of them is the dynamic nature of language in transition. Yet children are taught in Zulu today in South Africa, and Kenya has adopted Swahili as a national language and a medium of instruction.

The public debate that stoked the ire focused not on the fact of language change, but on the complete needlessness of language education that is not based solely on the colonial tongue. (I’ve hosted a similar debate on this blog once before. Today in Nigeria, English is as much a local language as it is a foreign one). It is a medium of instruction in all private schools and in most public schools. By the end of university education, one is expected to have acquired the sufficient proficiency of a native English speaker capable of conducting future life activities in any English-speaking environment. This is the ideal, but it is very far from the reality. Universities in Nigeria today send out hundreds of graduates many of who are not only incapable of communicating in English, but are also incompetent in their areas of supposed expertise. An experiment conducted in Nigeria in the 90s, seeking to find a correlation between native language instruction and good education, came down strongly on the side of native language education in the first three years of primary education as the best way to start children up; and native language along with English in the following three years of primary school as a perfect transition for them into the world of schooling. The result from the subjects show an overall positive trend in academics for those who learned first in their native language. The rationale is/was that the most crucial stage of learning is best dealt with in the language that the children are most familiar. In Nigeria today for most families from north to south, it is the mother tongue. This hypothesis, I should add, has been tested, verified, and supported by linguists and language policy makers from all around the world. Read this.

The use/purity of English, being already accepted as a Nigerian language, is under threat not by the presence of about 521 other languages in the country, but precisely because of inadequate attention to the use of those other languages. I have looked around the world – as even the creative writing field proves it over and over again – those who perform best in their native languages (reading and writing) are usually those who write best in any other language they acquire. It is no coincidence that the only (and best, of course) English translation of the most famous, most poetic, Yoruba literary offering of all time (Ogboju Ode Ninu Igbo Irunmale) was also done by the man now acclaimed as the best English writer to come out of Nigeria (and the winner of Africa’s first Nobel Prize for Literature). Salman Rushdie speaks (and from what we know, writes) Hindi with the proficiency of great Indian greats, but he is known in the world today mostly because of his contribution to the world of literature in English. None of this is an argument against English education as it is a strong defense of the need to equip children with the means of expressing themselves first in their native tongue to the best of their ability before a transition into any other language, including English.

One of the other recurring arguments is that English is the language of success. It’s an oft-repeated falsehood. And while spending valuable time disputing the charge is easily dismissed by someone pointing to the fact that I’m writing this in that same language, the real response stares us in the face: that inventions made in the corners of Berlin in German, or Osaka in Japanese, or Nnewi in Igbo are not thus undermined by their creator’s inability to communicate in English. Lamidi Fakeye – one of Nigeria’s best and most famous sculptor (died in 2009) wasn’t proficient in English, but he spent the better part of his old age being feted around the world for the breath of his works. J.M.G Le Clezio who won the 2008 Nobel Prize for literature wrote in French. Dante was Italian, and Freud spoke German. When Israel was founded in 1948, its Hebrew language that had already become “diluted” from use in different European countries became standardized and taught at different levels of education. The result has not been the extinction of English in Israel today, but a more robust upbringing for its citizens who have to participate in global dialogue. Language is an embodiment of our ways of life, and imbibing it in children at an early age has never done any harm to anyone.

As far as Nigeria is concerned, besides the worry about deepening ethnic divisions (a charge that falls down in the face of continued crises in spite of the use of English – the supposed “unifying” language and continued crises even in places of homogeneous language use), the only argument left is that English is the most superior language known to man, and that we (different from other culture in the world) lose from non-assimilation. This stems from a pervasive inferiority complex, and it fails too. (There’s no other way to explain why the US government spends its taxpayer monies providing Yoruba as a course for its university students, and why students so enthusiastically sign up for the class to learn the language, while supposed educated citizens of the country of the language’s birth spend their energy denigrating the teaching of said language to improve proficiency among primary users even when it has been shown to contribute to better academic development).

The only thing left to say then is the obvious: that this is not even a rejection of English – far from it – but a strong defense of the benefits of indigenous language teaching at the early age of life as a strong foundation for academic and literary success. Today’s NY Times makes a good defense of bilingualism as providing more than just literary access. The effects on the brain are equally encouraging. The competing forces of socialization will eventually modify each person’s upbringing along certain lines into adulthood. We have no control over that. Those who choose not to learn/speak English (or find themselves not learning or speaking it, for whatever reason) will evolve along their own chosen lines as well. But we owe those who go through the educational system to learn in their native language when possible (usually for the first six years of school). What will withstand the test of time is a strong foundation rooted in an upbringing that is tested and trusted. There is no dictionary in the world today in which literacy is defined in terms of one particular language. Every one of us has a grandfather or relative who, though unable to speak or write in English can do so perfectly in their first language. I do. He is a smart man, and he is a very successful man by all standards.

“One does not inhabit a country,” Emile M. Cioran says. “One inhabits a language. That is our country, our fatherland – and no other.”

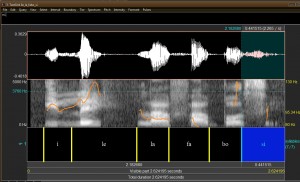

Having taught Yoruba at the university level for a while here in the States, it was natural to be interested in phonological and pedagogical dimensions of the language acquisition. Then I took a course on Second Language Acquisition with all its arguments on the critical period hypothesis that implies that language learning becomes difficult or impossible after a certain age. It all coalesced at some point in my head, and here I am. The data gathering part of the work itself is almost done, and the writing is halfway done already. I have discovered very many fascinating things, and encountered enough data to advance into a few more research directions in the future. One of the main things, of course, is that nothing at all prevents anyone from learning and acquiring tone or any language at any age whatsoever. There are influences of first language, to be sure, but they don’t pose enough challenge to prevent a subject (even those above the so-called critical period) from acquiring the form.

Having taught Yoruba at the university level for a while here in the States, it was natural to be interested in phonological and pedagogical dimensions of the language acquisition. Then I took a course on Second Language Acquisition with all its arguments on the critical period hypothesis that implies that language learning becomes difficult or impossible after a certain age. It all coalesced at some point in my head, and here I am. The data gathering part of the work itself is almost done, and the writing is halfway done already. I have discovered very many fascinating things, and encountered enough data to advance into a few more research directions in the future. One of the main things, of course, is that nothing at all prevents anyone from learning and acquiring tone or any language at any age whatsoever. There are influences of first language, to be sure, but they don’t pose enough challenge to prevent a subject (even those above the so-called critical period) from acquiring the form.