I figured that it’s been long since I last put up a photo post, so here – a few random shots mostly taken in our neighbouring state of Missouri.

I figured that it’s been long since I last put up a photo post, so here – a few random shots mostly taken in our neighbouring state of Missouri.

My left arm hurts from a TD immunization injection. I’m resolved to blogging about it only because all those darlings I’ve approached for petting the said hand to health have turned it down or have kept quiet and I’ve been left to my own devices: rest, and vulnerability, like a little boy returning from his first hospital visit 🙁 .

The only memorable thing to say was that I paid $6 for said shot, and I have become the last person to do so. As from tomorrow, people approaching the University Health centre to take the shots would pay up to $39. For the first time in over a decade, the State of Illinois is withdrawing subsidies on this service to students and the University Health Centre, as they told me yesterday, will now have to buy the medication by themselves at market value, and sell to students at market price.

It’s the economy, stupid. I’m sure that students won’t be smiling from the Health Centre anytime soon. Not international students at least, many of whom are studying on very limited personal funds. Neither does it help that this mandatory expense is not covered by the $500 per semester compulsory students Health Insurance policies.

Well, well. Here is a question requiring a whole article of its own, and I’ll tell you why. “African traditional religion” doesn’t quite exist. If you meant “Yoruba traditional religion”, I would still have a hard time answering you because the traditional Yorubas believed in so many things. In some cases, there were as many religions as there were family compounds, and each person believed in different things and worshiped them subsequently.

What I can say however is that there were some popular beliefs that have survived colonial intervention and modernity and are still being observed today in form of a system of belief. Their “holidays” are not usually public holidays but are usually marked with fanfare and festivities.

One of them is the Osun Osogbo Festival which is celebrated for about seven days in July/August in Osogbo, Nigeria. The festival is meant to celebrate a season of renewal and rebirth and it include dances, singing, and a ceremonial pilgrimage to the river Osun behind a virgin votary, the Arugba. (See photos from a previous Osun Osogbo festival here).

I also know of the Olojo Festival in Ile-Ife, and the Oke ‘Badan Festival in Ibadan which are also annual events.

On reflection on the coming milestone in Nigeria in the coming days, I came to the conclusion that one of the biggest drawbacks in the national progress till date is the poor handling of the country’s diverse ethnicity condition. For many years, I’ve wondered what it would have been like to live in the times of Tafawa Balewa, and Nnamdi Azikiwe, and Obafemi Awolowo, and the many other earlier nationalists that struggled for the nation’s independent many times from ethnic, but for the most part from nationalistic, standpoints. Eventually, I get to wondering how things could have gone wrong.

Tafawa Balewa remains one of my most admired men of those times not because I knew him, but because I didn’t, and because he was killed for no reason I could easily understand. And because he was one of the brilliant educated northerners who managed to get into the position of authority. And he was a simple man. Yet he was killed. Azikiwe was another one who became the opposition leader in a Western House of assembly in 1952 as a Nigerian and not as an Igbo man. When I think back to how things could have been different if the first coup hasn’t happened, or how things could have been if the coup had been bloodless, or if it had not had an ethnic slant, I sigh and get back to doing something else. Because I wonder if something beautiful and great could have evolved.

On invitation, I have written a post on my reflections on Independent Nigeria at 50 for the Nigerianstalk.org website. There are a few new posts there also by other Nigerian bloggers and I cherish the opportunity to join those distinguished folks in sharing my thoughts with the new generation of Nigerians to whom the future belong. I am not feeling as giddy as the government wants me to feel about these celebrations just yet, not surprisingly. I guess it’s because the country wasn’t born in 1960 anyway, and neither were those who had evolved their different ways of living together even long before any foreign forces stepped foot on the land area we now call our own. If 50 years of independence from the British could still be counted as an achievement, I guess it is a memorable milestone. In any case, check out the Nigeria@50 post series on Nigerianstalk and leave comments when you can.

The title of this post is premature, but I’ll leave it as that anyway. Monday was my first time as a volunteer teacher of English at the International Institute so I can’t tell you much about the life of a volunteer. The last time I volunteered for something similar was teaching up north in a Nigerian secondary school a lifetime ago. But that was different not only because it was mandatory but because the subject of that experience were young children who already have some exposure to the English language but only needed to improve on it. This time, I’m dealing with those who had never had any exposure to speaking, reading or writing English but are willing to put themselves through the stress of acquiring it, even at advanced age.

The International Institute in St. Louis is set up to cater for refugees, immigrants and new comers into the United States who do not yet have sufficient knowledge of the English language. Some of them were hearing English being spoken for the first time, many of them never opened a book, and most of them were holding a pencil, and learning to write for the very first time. Volunteers come from different parts of the country and I had heard last week that the Institute would be closing down its adult literacy program as well as the citizenship classes for lack of funding from the government. Yesterday it was confirmed that Institute has just received new funding to continue the programmes, particularly adult literacy one, and so it would continue though the citizenship classes may not.

The International Institute in St. Louis is set up to cater for refugees, immigrants and new comers into the United States who do not yet have sufficient knowledge of the English language. Some of them were hearing English being spoken for the first time, many of them never opened a book, and most of them were holding a pencil, and learning to write for the very first time. Volunteers come from different parts of the country and I had heard last week that the Institute would be closing down its adult literacy program as well as the citizenship classes for lack of funding from the government. Yesterday it was confirmed that Institute has just received new funding to continue the programmes, particularly adult literacy one, and so it would continue though the citizenship classes may not.

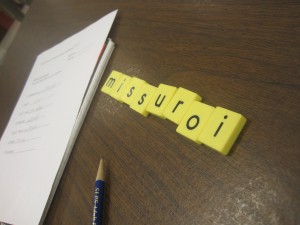

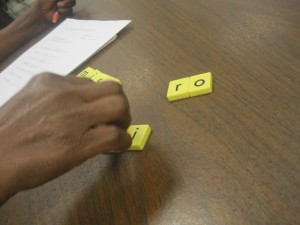

The classes have a very elementary syllabus, as would be expected of a class with such level of student proficiency. The students range in age from thirty to sixty-five and they come from different parts of the world. Our job was to help them read and gain sufficient literacy needed to survive in such a country as this. The books had stories that were easy to read and understand. They also came with pictures, as they should be, and each reading experience was one-on-one, with the students reading along and trying to link text with pictures and ideas. It brought smiles to my face to see grown people show that much enthusiasm to reading. We also did some word scrambling and a few phonic exercises.

The classes have a very elementary syllabus, as would be expected of a class with such level of student proficiency. The students range in age from thirty to sixty-five and they come from different parts of the world. Our job was to help them read and gain sufficient literacy needed to survive in such a country as this. The books had stories that were easy to read and understand. They also came with pictures, as they should be, and each reading experience was one-on-one, with the students reading along and trying to link text with pictures and ideas. It brought smiles to my face to see grown people show that much enthusiasm to reading. We also did some word scrambling and a few phonic exercises.

What delighted me most is the enthusiasm and confidence of the students at learning. Many of them had been displaced by hard circumstances in their country of birth and had now come to acquire new means of communication in order to survive in a place away from home. They come with their own survival instincts and a rich reservoir of life experiences, but they can’t express them to us because we don’t speak Swahili, Dzongkha/Bhutanese, Spanish, French, Ewe, Gen, Kabiye or any of the languages they speak where they come from. Nor do we want to. It promises to be a rich teaching/learning experience.