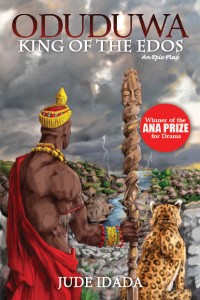

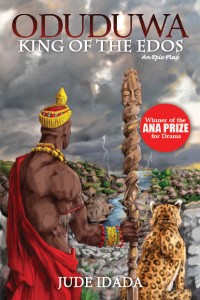

Jude Idada is an award-winning screenwriter, author and playwright. His epic play, Oduduwa, King of the Edos won the 2013 Association of Nigerian Authors’ Prize for Drama and has been short-listed for the 2014 NLNG Nigerian Prize for Literature. In this conversation with Servio Gbadamosi, Idada discusses the work, shares some of the back stories that fuel his creativity and comments on critical national issues.

You have written prose, poetry and drama—the three genres of literature, all with significant strength. How does it feel straddling the three genres? Which of the three would you consider your favourite genre?

I will say that writing for me is first and foremost second nature. The genres of expression is more or less that which best captures most completely the theme I am exploring and espousing, coupled with it having the capacity to enthrall the reader most effectively.

In terms of the feeling it gives me, I will say, it is empowering, like a surgeon who has the choice from a plethora of knives to do his work. It enables choice, and choice of course is a weapon of freedom.

I had primarily started writing prose at the age of seven, completing my first novel at the age of nine. I think it has a foundational sentiment to me, even though that which naturally comes to me is drama, but in terms of my favourite genre both as a creator and consumer, I daresay is prose because of its ability to explore and express without the confines of multiplicity of characters, time and space.

Your epic play, Oduduwa, King of the Edos captures the endless struggle between convention and logic and reflects on man’s continued search for meaning and relevance in the world around him. How much of the book would you describe as fiction, and how much was gleamed from your research into pre-existing origin narratives?

Owing to the time explored in the play and the pre-existing narratives concerning that time, I had to deal primarily with oral tradition which owing to the paucity of facts was itself mythical. Therefore, in the play, there is fiction, which was the thread that weaved the dramatic narrative together and then there was faction, which was the weighted narratives from both parts of the divide, parts being the Edo and the Yoruba belief pantheon.

Owing to the time explored in the play and the pre-existing narratives concerning that time, I had to deal primarily with oral tradition which owing to the paucity of facts was itself mythical. Therefore, in the play, there is fiction, which was the thread that weaved the dramatic narrative together and then there was faction, which was the weighted narratives from both parts of the divide, parts being the Edo and the Yoruba belief pantheon.

That being said, the existence of the main personages and locations of the play would by and large be accepted as real, since oral tradition in itself is not completely fake, and thus was a mode of storing and transferring information in the days of old, sometimes surviving to these times in the forms of the storytelling of the griots of Gambia and Senegal.

In the light of this, the comparative dramatic analysis of both narratives of the Oduduwa personage was done using the “what if” model… what if you believe this, because of this… and this was a two–sided exploration using widely accepted beliefs as the base information or knowledge pool.

Suffice to say that the ratio of veracity and mendacity of the play is a grey area, being that the play is an amalgam of cultural truths, anthropological truths, and archaeological truths. It also contains accepted truths, believed truths, assumed truths, common truths and dramatic truths.

The play was awarded the 2013 Association of Nigerian Author’s Prize for Drama and has been short-listed for the 2014 NLNG Nigeria Prize for Literature, what would you say has been responsible for the success of the book?

I would humbly posit that it is the humanity of the play and the believability of the characters, their motivations, challenges, strengths and weaknesses. It does not pontificate or pick sides but dramatically forwards a “what if” analysis of two competing belief systems, asking the reader or the viewer to think deeply and widely with an open mind.

I ask this because of the play’s attempt at drawing congruence between the diverse oral narratives on the origin of the protagonist, Oduduwa. Could it be that the age-long debate and controversies surrounding Oduduwa’s ancestry have somehow drawn attention to the book?

The controversy itself as occasioned by the stormy reception accorded the writing of the memoirs of the Oba of Benin, I Remain, Sir, Your Obedient Servant birthed the writing of the play, so since it is a debate that will rage for time unknown, there will normally or naturally be interest in any material that sheds more light or espouses the contending issues of the argument. So, yes, some of the interest in the play surely stems for the debate concerning the origin or identity of Oduduwa, but I hope that the play in itself would overtime rise above the debate and hold its own as a piece of good theatre, both in the written form and as performance art.

An earlier version of the play was staged at the Arts Theatre, University of Ibadan in December, 2007; are we going to see the play on stage again anytime soon?

Yes, there are advanced plans to stage a command performance that will hopefully tour some cities in Nigeria, but before that, a stage reading is being planned in Lagos.

At the beginning of the play, we are confronted with the language of judgement, war and bloodshed while at the ending, we are filled with peace and our faith in humanity’s ability to redeem itself is reassured. At this turbulent period in our national life, what does this portend for our nation?

Primarily it seeks to reassure us that we are not bound to the failings of our past, neither is our future wholly predicated on the worst in us. But if we band together, learn collectively from our mistakes, we can through tolerance, understanding and love for one another, find a way to the light of redemption through the darkness that has befallen us.

Primarily it seeks to reassure us that we are not bound to the failings of our past, neither is our future wholly predicated on the worst in us. But if we band together, learn collectively from our mistakes, we can through tolerance, understanding and love for one another, find a way to the light of redemption through the darkness that has befallen us.

It shows us that traditions and cultures that are hinged on the learned experiences of the past has its value, but these should also be subject to the dynamics of change, because that which does not work should be set aside for that which works- notwithstanding the sentimental value it holds to the people. Since culture itself is a total way of life of a people that is dictated by the demands of the times, when the time changes, culture should follow suit. Therefore, for us as a nation to be able to shout Uhuru, in the foreseeable future we must look inwards and weed from ourselves the cantankerous habits or practises that has pulled us behind, divided us and caused us to fall into a developmental inertia. We must embrace the inclusiveness, oneness and pragmatism that are hallmarks of a successful nation, so that at the end of our struggles, we can say, yes our past had its pitfalls, but through our logical reasoning and progressive introspection we have surmounted that which has hindered us, and now our future is secured, because we have learnt who we once were and its failings, we know who we currently are and our challenges and are assured with a certainty who we want to be and its infinite possibilities.

I ask because of the argument about the role of literature and the arts in society. Beyond the essential duty of interrogating our past, present and forging a vision for the future, how else can writers and artists help in driving change in developing countries like Nigeria?

I believe it transcends the creation of art, but the living out of our creative postulations. We must not only use our pens as warriors but also use our lives as examples. As Professor Wole Soyinka and his likes have done, we must step into the ring of social discourse and engage, we must march with the oppressed and champion the marginalised; we must defend the rights of the ostracised and engender the culture of tolerance of the individual natures and the collective desires.

Just as we see Arundhati Roy stand in front of the fray and confront the institutions of power in India, or Nadine Gordimer not only talk the talk but also walk the walk in South Africa. Gabriel Garcia Marquez also confronted the engines of capitalism on behalf of the poor in Colombia, we as writers or artistes must do same in Nigeria. We must not only be seen basking in the glow of the success of our works but actively living out the fight for the preponderance of the best in us and the success of our socio-political and cultural realities, as we want to know it.

As a documentarian, you will agree with me that there is paucity of documentaries made by Africans. Most of what we have as documentaries of our past, and even our present, are made by people and firms outside the continent. Ironically, our movie industry keeps flourishing. What are the factors responsible for this and how do we begin to bridge the divide?

Documentaries unfortunately do not enjoy the mass appeal of fictional cinematic narratives and thus exist as a scholarly or educational pursuit, which in itself is a niche industry, which implies a very low return on investment. This explains why the consumption is low and the practice is even lower in the Nigerian landscape.

Funding for documentaries is also largely external and primarily provided by Non Governmental Organisations who are more interested in exploring issues that pertain to us, than we are about ourselves. This is a sad commentary but a very truthful one. In cases where it is funded locally, it is commissioned by corporate bodies and the subject matter revolves around their own activities, ambitions but rarely on issues of national concern, thus the consumption is limited to their clients, shareholders or employees, this does not grow the field of national consumption.

To bridge the gap, we have to realise that the funding has to be non-profit geared, be both government and private industry generated. Quota systems have to be created in the broadcasting policies which includes television and cable, so that there is a home for the documentaries produced. Censorship of such documentaries must be informative and not punitive, so that relevant issues can be explored.

Companies must begin to be assess and promote documentaries by their social corporate governance and how they engage on issues that do not necessarily reflect on their products but on the collective well-being of the society, so it is not enough to sponsor talent shows but what you do to educate and enlighten the citizenry.

It will be foolhardy to believe that people will gravitate towards documentaries as they do to fictional motion picture, because there is nowhere in the world that this obtains. But there is a dearth of documentaries in Nigeria and this is an anomaly that must be addressed, but the salvation rises squarely on the government and private institutions, for once funding and platforms of distribution are created, the filmmakers will gravitate to this medium of artistic expression.

How has technology and new media impacted your creativity? Have you any fears that the growing adoption of mobile hand-held devices will impact negatively on our reading culture and social interaction?

I can no longer write long hand neither can I physically go through a dictionary or a thesaurus… the ease of writing is phenomenal and very well welcomed… research is easier, collaboration is done with much ease… the mode of sharing and distribution of your work is right there at your finger tips and you do not face the constraints of time or space… the world has become my oyster… it is a golden age to be a writer.

That being said, there is no gainsaying the fact that there is a reducing number of readers of traditional literature because of the competing mediums of entertainment. The challenge however is that the fad of “being scholastically dumb is cool” and that is being championed by the youth of today.

Hence as a writer while I am exploring the use of multi-media to make my work interactive, I have to also make sure my works transverse media, genre and the issues and language are accessible and relatable, knowing full well that the ones who must read will read, the ones who have not been exposed to the joy of reading might read, and the ones who do not read or have no interest in the power of the written world, will not read.

What authors have had a major influence on your writing career? What advice do you have for young, upcoming writers?

Being that my writing began at an early age, my formative writing skills were formed by voraciously consuming the works of Enid Blyton, Roald Dahl and the multitude of writers of the Pacesetter series. I then advanced to the Heinemann African Writers Series. That being said, I discovered a new academic level of interest and cultural congruence in the prose of Chinua Achebe, the drama of Wole Soyinka and the poetry of David Diop, but I soared as an eagle when I first read Ben Okri’s Famished Road and discovered a unique voice and the world of magical realism. When I read the works of Marie Correlli, I discovered the genius of combining high art with accessible art. Through several years of reading Ian McWan, I found the electricity of live dialogue and slowly began to find my own voice, a voice that has resonated through all the media I have used.

I would not be voluble in my advice, here I go, writers read widely and voraciously, write incessantly and rewrite even more. They develop a thick skin and believe in themselves because many a disappointment will people your way. Trust your voice and polish it. Find your style and champion it; find your conviction and live it out. Most importantly embrace the dynamics of the age, and use it to your advantage, for no one fights a battle in these times without the ferocity of a bayonet.

For a lot of young writers and aspiring writers, it was a platform to learn one or two tricks in the writing craft. The reknowned poet, Jumoke Verissimo with support from WriteHouse Collective and PEN Nigeria had opened a creative workshop for poetry last month. The second edition of the workshop which held on Saturday, 20th of September delved into the idea of experience as a vehicle for poetry and the use of metaphors.

For a lot of young writers and aspiring writers, it was a platform to learn one or two tricks in the writing craft. The reknowned poet, Jumoke Verissimo with support from WriteHouse Collective and PEN Nigeria had opened a creative workshop for poetry last month. The second edition of the workshop which held on Saturday, 20th of September delved into the idea of experience as a vehicle for poetry and the use of metaphors. Jumoke asserted that there is absolutely nothing like a ‘writer’s block’. She said that if one could generate a first line based on personal experience, a second line would ‘flow from the bones’ and a third line will be accomplished easily. Other participants were actively involved as they contributed to the analysis of each other’s work.

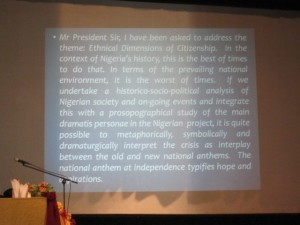

Jumoke asserted that there is absolutely nothing like a ‘writer’s block’. She said that if one could generate a first line based on personal experience, a second line would ‘flow from the bones’ and a third line will be accomplished easily. Other participants were actively involved as they contributed to the analysis of each other’s work. Verissimo delved into metaphors as a form of experience, ‘you need to make a metaphor of your life, you place two things that are different and try to make a connection between them. As a poet you have created that metaphor, and then we will begin to see our lives, through that metaphor. Verissimo said. She also recalled her stint with Farafina ‘I remember working for Farafina, and the day we were working on the magazine and we were trying to contact Mr (Igoni) Barrett to send us a story then and he said that ‘he wrote poetry first before he began to write stories’. She said ‘poetry helps you as a writer of prose, metaphors helps your imagery and interpret an experience’. Participants were also encouraged to create metaphors spontaneously in order to sharpen their creative prowess.

Verissimo delved into metaphors as a form of experience, ‘you need to make a metaphor of your life, you place two things that are different and try to make a connection between them. As a poet you have created that metaphor, and then we will begin to see our lives, through that metaphor. Verissimo said. She also recalled her stint with Farafina ‘I remember working for Farafina, and the day we were working on the magazine and we were trying to contact Mr (Igoni) Barrett to send us a story then and he said that ‘he wrote poetry first before he began to write stories’. She said ‘poetry helps you as a writer of prose, metaphors helps your imagery and interpret an experience’. Participants were also encouraged to create metaphors spontaneously in order to sharpen their creative prowess.