Peter Akinlabi was the winner of the Sentinel Literary Quarterly Poetry Competition in October 2009 with his poem, Moving. He holds a B.A degree in English from University of Ibadan and an M.A in Literary Studies from University of Ilorin. Peter currently lives and works in Ilorin. I had this conversation with him via email.

________

Tell me about your involvement with poetry. How long have you been writing and how did it all start?

I record no precocity here, as it were. My involvement in poetry began as a love for creative use of language. I started writing after high school, however. The space of time in-between high school and higher education, when you generally cast about for something to do while waiting for WAEC and JAMB results. I read a lot of stuffs then, Fagunwa mostly, books in Heinemann African Writer Series. Obi Egbuna’s The Rape of Lysistrata was a long-lasting influence in this phase- have you ever heard of the author or the book? So was my threadbare copy of K.E Senanu and Theo Vincent. Ulli Beier’s edited collection of African poetry was like an appendage to my body.

I wrote short love poems for a girlfriend, lifting words and expressions from impossible sources as diverse as Helen Ovbiaghena, Shakespeare, Kwesi Brew, Lenrie Peters, Dennis Brutus and other poets in recommended high school anthologies. Later I encountered Alagba Opadotun’s Arofo, Soyinka’s Idanre and Okigbo’s Labyrinths. Things changed from there. I started thinking of poetry beyond juvenile, amorous verse. Then I went to study Literature in English in the university.

Have you always had a preference for poetry or that just happened to be your first love?

Poetry is my first love. I love fiction. But I knew if I decided to do fiction I probably would write only one novel in my lifetime. This is because I would love to write the kind of stories I like to read – stories that can elevate consciousness, that can torpedo the base of creative expectation; stories that can eternalize reality. I love profundity in fiction… Fiction that blurs boundaries of consciousness. I would write the first draft at say 25 and would perfect it for another 30 years. But I could write a poem in 5 minutes and perfect for a month, a year, but I surely would have written more poems in between. I wonder how long it took Yvone Adhiambo Owuor to complete ‘The Weight of Whisper’.

How much did Yoruba language influence your writing?

A great deal. Thing is I started speaking English when I was about fifteen years old and in third year of secondary school- you know how township public school could be like. But by then I had read through all Odunjo’s Alawiye texts, Oju Osupa series and all Fagunwa’s novels.

Then I grew up in a context of Yoruba artistic practices. I grew up amidst daily rehearsals of Ijala Poetry by my uncle Ogundare Foyanmu and his group. The way they bantered words gamely in their discourse of abuse was especially a delight. Then the annual Egungun festivals and the attendant cultural spectacle- especially the Iwi. I picked a formidable bit of Ifa poetry from another uncle who was a diviner chieftain. I was also introduced to the beautiful poetry of Lanrewaju Adepoju, Odolaye Aremu and Olatubosun Oladapo at this time.

Yet what Yoruba language gave me, and still gives me, is a gift of imaginativeness, of transgressive conception of worldview through language. The material of my poetry is not essentially Yoruba, but the ontology is.

Who are your Literary Influences and just how much have you taken from them?

Early influences in poetry are Soyinka and Okigbo and they still remain constant creative founts for me – I mean how can you possibly get over Idanre or ‘Distances’? But I would soon discover a dizzying poetic experience in the university: Russian poetry- especially Mayakovsky; American- Walt Waltman, Brodsky, Allen Ginsberg; English- ah, Auden, Plath; Irish-Yeats, Seamus; African American- Sonia Sanchez, Langston Hughes Caribbean- Walcott, Braitwaite and the spaniard Garcia Lorca. Then a very important poetic influence is this book of creative non fiction by Harbison called The Eccentric Spaces.- that book makes you see the godhead in a most prosaic object. Then time froze, when I discovered Jay Wright- I unearthed a poetic joy on the strength of only one collection- Boleros- a book of exceptional beauty and elegance. Recently, I go back often to Mani Rao, the Hong Kong poet of Indian descent, I call her poetry deep and rumbling stillness of waters. Niran Okewole and Benson Eluma rupture the box; I read them as some read the stars – to see.

How many poems have you written so far, and where have they been published or pending publication?

I am lazy. I am slow. I am careful. I only push a poem out when I have convinced myself and some of my friends that it is fit for the public. I once wrote a ‘yab’ poem titled ‘To a Poet Manqué’, you see, deriding some poetaster who thought he was Okigbo of some sort. I have poems scattered in all sorts of places. But I am slow and careful in working my poetry, my process is kind of sculptural. And I believe some of my poems will appear in major literary e-zines in coming months.

What influenced your Sentinel Poetry winning poem ‘Moving’?

That poem mediates the experience of loss, memory and creative replication of place that attend all migration, especially when relocation is threatening and sudden as the expulsion of Nigerians from Ghana in the late 60s was. My family was a victim of such forcible uprooting, though they called no where else home but Kumasi, Ghana, since 1940s. There is a bit of fetish pain in trying to reconstruct places only others remember. ‘Moving’ reconstructs the Kumasi experience.

How did you feel when you found out you won the competition?

No grandiose feeling, really. That was not my first literary prize. There was the Okigbo Poetry Prize of the University of Ibadan, a later edition of which I believe you too won. It was initiatory, you know, you felt confirmed. But then Sentinel comes with a cash prize- that delighted. The elation really was later when I found out I was the first Nigeria to win it. The absolute pleasure is the opportunity to step on such large stage as the Sentinel team provides. We thank them.

Describe the nurturing of your creative development at the University of Ibadan. What stood out in your memory?

The library. The books. That was the first time I was seeing so many books and I must have thought some fire could consume the library if I didn’t finish reading the book early enough. The library offered me the first, initiatory companionship on encountering UI. I, however, was jolted out of the ritual when I almost got expelled for dismembering a book. Then, the faculty. There were some of the academic staff whose sheer presence can revolutionize creative or artistic genes in you. But what actually blessed my days were contacts with some colleagues, fellow students, whose creativity and conviction, in different ways, gave me a sense of direction and commitment.

How would you rate the quality of literary offering in Nigeria today and the climate of literary production?

Terrific. Absolutely.

What brings you inspiration?

Every thing that lifts reality out of the mundane. To misquote Tom Robbins, Everything that amplifies the whisper of the infinite until it’s audible.

What is the state of the literary scene in Ilorin where you now reside?

Non-existent. I live in Ibadan as far as literary creation goes. And Ibadan is really a mouse click away, you know.

Do you see any hope for the renaissance of literary development in Ilorin anytime soon?

Well, Ilorin has never been known as a literary city. There are three important literary figures I know of in Ilorin currently, however- Olu Obafemi, the playwright, Charles Bodunde the poet and Abdurasheed Na’allah. Incidentally all of them are also very busy academics. I am not aware of younger or aspiring writers in the town who can push the word rolling. And I have not heard of any writerly group either.

What are your creative writing plans for the future?

I hope to publish a collection of poems as soon as I could arrange my time and pen for the purpose. While I work on that, I surely would continue to engage the various literary avenues the internet can offer creatively.

Thank you for taking time to talk to me.

Thank you for the opportunity.

Where I come from, there is no Halloween. We have masquerades. My last memorable trip to my grandfather’s village in Ogun state Nigeria was when I was barely a teenager. It was a festive period, and it always came with a carnival of masques, mostly manned by youths of around and a little above my age. Many of the masquerades there always went with whips and canes sometimes to scare, and sometimes as a ritual part of the carnival experience.

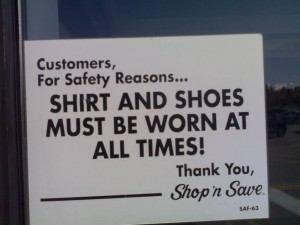

Where I come from, there is no Halloween. We have masquerades. My last memorable trip to my grandfather’s village in Ogun state Nigeria was when I was barely a teenager. It was a festive period, and it always came with a carnival of masques, mostly manned by youths of around and a little above my age. Many of the masquerades there always went with whips and canes sometimes to scare, and sometimes as a ritual part of the carnival experience. “Shirt and shoes must be worn at all times!”

“Shirt and shoes must be worn at all times!” But it was while returning, alone, at night that I had another one of my travula moments. I got to a traffic light that showed red, and I brought out my camera to immediately capture the contrast of the colours against the darkness of the night, only to hear some voices from inside a car on the road, also waiting for the lights to change, screaming in my direction.

But it was while returning, alone, at night that I had another one of my travula moments. I got to a traffic light that showed red, and I brought out my camera to immediately capture the contrast of the colours against the darkness of the night, only to hear some voices from inside a car on the road, also waiting for the lights to change, screaming in my direction.